When meeting with other attorneys at practice seminars, I frequently hear comments like, “I don’t represent individuals” or “I won’t take a case worth less than [fill in the blank].”

When meeting with other attorneys at practice seminars, I frequently hear comments like, “I don’t represent individuals” or “I won’t take a case worth less than [fill in the blank].”

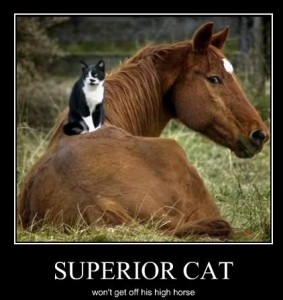

You may have decided that under your business model it doesn’t make sense to take on small cases, and there is some wisdom to that thinking. A small matter can require nearly as much administration as a complex case, and some cases just cannot be economically prosecuted. Similarly, an attorney who handles major medical malpractice cases probably does not care that she could also be making money with slip and falls, because those cases might negatively impact her brand. But with that said, don’t get so high on your horse that you miss some very lucrative opportunities due to preconceived notions.

I used to eschew cease and desist and demand letters. Potential clients were always calling to ask that I send a letter, but I usually sent them to fresh out of law school attorneys that I knew needed the work. The problem was that I had always administered these small matters like any other case, setting up a file, creating a directory on the server for the client, putting the client in the billing system, providing a fee agreement, and meeting to discuss the issue. For the relatively small fee, it just didn’t seem worth it, given the administrative aspects.

But then I devised a simple system that basically eliminated all that administrative aspects. At the conclusion of the initial telephone call, I email the client a simple one-page fee agreement which captures all their contact information, eliminating even the need for a client intake form. Under the fee agreement, I charge $495 per hour with a two hour minimum. For awhile I did them as flat fees, but that occasionally created a problem when the assignment would morph into something bigger, as in the case where the letter had its intended effect, and I had to prepare a settlement agreement or such. If I had to prepare a second agreement to cover the additional work, that defeated the streamlined approach. Now, I set them up as an hourly arrangement with a two-hour minimum. The vast majority of the time, this arrangement is the same as a flat fee. The agreement provides that absent any unforeseen circumstance, I do not anticipate that the assignment will take more than two hours, but in the event the assignment does turn into something greater than writing a letter, those additional services are covered.

The client pays the deposit of $990 up front. Since the fee is paid, we never need to put the client “in the system.” I handle the whole thing with a single manila folder, writing notes on it as I go.

Understandably, some clients respond with, “two hours for a letter?!”, because they envision that the process involves only sitting down to bang out the actual letter. To address those concerns, when I send out the fee agreement, I attach a PDF I created entitled “21 Steps to a Demand Letter,” which explains that sending out a simple letter includes discussing the matter with the client, drafting the letter, providing it to client for approval, emailing it to the individual or business, reviewing the email from the individual asking for more time to respond while they retain counsel, emailing the client to explain that more time has been requested, reviewing the email from opposing counsel, stating that he has just been retained and asking for more time to respond, etc. Obviously all these steps do not arise in every situation, but the PDF educates the client as just how involved the process can be.

Understandably, some clients respond with, “two hours for a letter?!”, because they envision that the process involves only sitting down to bang out the actual letter. To address those concerns, when I send out the fee agreement, I attach a PDF I created entitled “21 Steps to a Demand Letter,” which explains that sending out a simple letter includes discussing the matter with the client, drafting the letter, providing it to client for approval, emailing it to the individual or business, reviewing the email from the individual asking for more time to respond while they retain counsel, emailing the client to explain that more time has been requested, reviewing the email from opposing counsel, stating that he has just been retained and asking for more time to respond, etc. Obviously all these steps do not arise in every situation, but the PDF educates the client as just how involved the process can be.

Some attorneys will snort and say that $990 is not worth the hassle, but this is short-sighted for a couple of reasons. If the letter does not accomplish the client’s goal and litigation becomes necessary, then who are they likely to hire? Getting paid to handle the preliminaries before getting retained to handle the case is a very good thing.

Then there is the math. The snorters usually change their tune when I do the math for them. I was turning a dozen or more of these requests every month. If I average just two of these letters per week, that adds $102,960 to my annual income. I know full time attorneys who don’t make that much annually. Plus, in some instances the letter generates an immediate phone call from the recipient, agreeing to comply with the request, and no further action is required. In those cases the my effective hourly rate is doubled. Who’s snorting now?

If you do start writing demand letters, be careful that you don’t develop a reputation as a letter writer who never makes good on any threats. One employment attorney I know sends demand letters that are a sight to behold, usually consisting of more than 20 pages (for which he charges far more than $990). However, he never makes good on this threat to sue, so attorneys familiar with him don’t take the letters seriously and he therefore provides little service to his clients in those instances. As a matter of policy, if my demand letter is going to threaten litigation, I won’t agree to do the letter unless the client appears strongly motivated to pursue litigation should the defendant not capitulate to the letter.

The point of this article is not that you should start writing demand letters. Given the nature of my practice, that happens to be a service that many clients request, but it may not be so in yours. The point, rather, is to get you to look at your own practice to see if you are turning away income streams because of some preconceived notion or inflated sense of worth. Do clients ever call you with questions you can’t answer without additional research? Don’t send them away; charge to look up the answer. Are you turning away contingency cases out of fears over collection? What about a hybrid arrangement with a reduced hourly fee plus a percentage? Do an audit of your situation to determine if you are letting money escape.

Incidentally, speaking of demand letters, once I started to do so many, they developed their own administrative issues. I keep them all separate from our litigation files, but stacking the files on my credenza wasn’t really workable and putting them in a file cabinet meant heading to said cabinet every time I got a call about one of the files. My partner came up with the fantastic idea of a rolling file cart. Now all these files are in the cart. I just pull it over when I’m working on a file, and shove it out of the way when I’m not. If I’m away handling a trial or whatever, one of the other attorneys can roll the cart into their office to check the status of all the pending files based on my notes, and follow up as necessary. I love this thing (simple mind, simple pleasures). You can’t really tell from the picture, but you can use the entire top for legal size hanging folders (that’s what I do), or about half for legal size and half for letter size. It even has cool basket drawers underneath, although I have yet to come up with a use for those. Some of these carts were crazy expensive, but this one was just 50 bucks, and it is built really well.

If you’re proceeding through my Starting Your Own Law Firm series, click on the big blue NEXT button to proceed to the next article. I’ll show you how rid yourself of many of the inherent money concerns with a new practice, by utilizing flat fees. Flat fees not only relieve you of collection problems since you get the money up front, but they free you to do what needs to be done on the case, without worrying whether the client thinks you are just running up the bill.

If you’re proceeding through my Starting Your Own Law Firm series, click on the big blue NEXT button to proceed to the next article. I’ll show you how rid yourself of many of the inherent money concerns with a new practice, by utilizing flat fees. Flat fees not only relieve you of collection problems since you get the money up front, but they free you to do what needs to be done on the case, without worrying whether the client thinks you are just running up the bill.

If you came to YourOwnLawFirm.com through this article, and want to get the full benefit of the site, then please click on the START button to begin at the beginning. I’ll show you step-by-step how to launch your first niche site. I’ll show you how just one of my static niche sites brings in over $100k per year. Get a few of those up and running, and you have yourself a thriving practice. If you already have a website where you are utilizing content marketing (or want to try something different), then here are some more articles on how to market your law firm.

If you came to YourOwnLawFirm.com through this article, and want to get the full benefit of the site, then please click on the START button to begin at the beginning. I’ll show you step-by-step how to launch your first niche site. I’ll show you how just one of my static niche sites brings in over $100k per year. Get a few of those up and running, and you have yourself a thriving practice. If you already have a website where you are utilizing content marketing (or want to try something different), then here are some more articles on how to market your law firm.